Osho narrated a beautiful story from Upanishad days about seeking supreme knowledge

(http://www.energyenhancement.org/vedanta/Osho-Vedanta-Seven-steps-to-Samadhi-Chapter-4-The-Supreme-Knowl edge.html)

It runs like this: The supreme knowledge cannot be taught. The disciple cannot know that there is something which cannot be taught. It happened in Upanishadic days that one young boy, Svetaketu, was sent by his father to a gurukul, to a family of an enlightened master, to learn. He learned everything that could be learned, he memorized all the Vedas and all the science available in those days. He became proficient in them, he became a great scholar; his fame started spreading all over the country. Then there was nothing else to be taught, so the master said, "You have known all that can be taught. Now you can go back."

Thinking that everything had happened and there was nothing else -- because whatsoever the master knew, he also knew, and the master had taught him everything -- Svetaketu went back. Of course with great pride and ego, he came back to his father.

When he was entering the village his father, Uddalak, looked out of the window at his son coming back from the university. He saw the way he was walking -- very proudly, the way he was holding his head -- in a very egoistic way, the way he was looking all around -- very self-conscious that he knew. The father became sad and depressed, because this is not the way of one who really knows, this is not the way of one who has come to know the supreme knowledge.

The son entered the house. He was thinking that his father would be very happy -- he had become one of the supreme most scholars of the country; he was known everywhere, respected everywhere -- but he saw that the father was sad, so he asked, "Why are you sad?"

The father said, "Only one question I have to ask you. Have you learned that by learning which there is no need to learn anything any more? Have you known that by knowing which all suffering ceases? Have you been taught that which cannot be taught?"

The boy also became sad. He said, "No. Whatsoever I know has been taught to me, and I can teach it to anybody who is ready to learn."

The father said, "Then you go back and ask your master that you be taught that which cannot be taught."

The boy said, "But that is absurd. If it cannot be taught, how can the master teach me?"

The father said, "That is the art of the master: he can teach you that which cannot be taught. You go back."

He went back. Bowing down to his master's feet, he said, "My father has sent me for an absolutely absurd thing. Now I don't know where I am and what I am asking you. My father has told me to come back and return only when I have learned that which cannot be learned, when I have been taught that which cannot be taught. What is it? What is this? You never told me about it."

The master said, "Unless one inquires, it cannot be told; you never inquired about it. But now you are starting a totally different journey. And remember, it cannot be taught, so it is very delicate; only indirectly will I help you. Do one thing: take all the animals of my gurukul -- there were at least four hundred cows, bulls and other animals -- and go to the deepest forest possible where nobody ever comes and moves. Live with these animals in silence. Don't talk, because these animals cannot understand any language. So remain silent, and when just by reproduction these four hundred animals have become one thousand, then come back."

It was going to be a long time -- until four hundred animals had become one thousand. And he was to go without saying anything, without arguing, without asking, "What are you telling me to do? Where will it lead?" He was to just live with animals and trees and rocks; not talking, and forgetting the human world completely. Because your mind is a human creation, if you live with human beings the mind is continuously fed. They say something, you say something -- the mind goes on learning, it goes on revolving.

"So go," the master said, "to the hills, to the forest. Live alone. Don't talk. And there is no use in thinking, because these animals won't understand even your thinking. Drop all your scholarship here."

Svetaketu followed. He went to the forest and lived with the animals for many years. For a few days thoughts remained there in the mind -- the same thoughts repeating themselves again and again. Then it became boring. If new thoughts are not felt, then you will become aware that the mind is just repetitive, just a mechanical repetition; it goes on in a rut. And there was no way to get new knowledge. With new knowledge the mind is always happy, because there is something again to grind, something again to work out; the mechanism goes on moving.

Svetaketu became aware. There were four hundred animals, birds, other wild animals, trees, rocks, rivers and streams, but no man and no possibility of any human communication. There was no use in being very egoistic, because these animals didn't know what type of great scholar this Svetaketu was. They didn't consider him at all; they didn't look at him with respect, so by and by the pride disappeared, because it was futile and it even looked foolish to walk in a prideful way with the animals. Even Svetaketu started feeling, "If I remain egoistic these animals will laugh at me -- so what am I doing?" Sitting under the trees, sleeping near the streams, by and by his mind became silent.

The story is beautiful. The years passed and his mind became so silent that Svetaketu completely forgot when he had to return. He became so silent that even this idea was not there. The past dropped completely, and with the dropping of the past the future drops, because the future is nothing but a projection of the past -- just the past reaching into the future. So he forgot what the master had said, he forgot when he had to return. There was no when and where, he was just here and now. He lived in the moment just like the animals, he became a cow.

The story says that when the animals became one thousand, they started feeling uncomfortable. They were waiting for Svetaketu to take them back to the ashram and he had forgotten, so one day the cows decided to speak to Svetaketu and they said, "Now it is time enough, and we remember that the master had said that you must come back when the animals became one thousand, and you have completely forgotten. Now is the time and we must go back. We have become one thousand."

So Svetaketu went back with the animals. The master looked from the door of his hut at Svetaketu coming with one thousand animals, and he said to his other disciples, "Look, one thousand and one animals are coming." Svetaketu had become such a silent being -- no ego, no self-consciousness, just moving with the animals as one of them.

The master came to receive him; the master was dancing, ecstatic. He embraced Svetaketu and he said, "Now there is nothing to say to you -- you have already known. Why have you come? There is no need to come now, there is nothing to be taught. You have already known."

Svetaketu said, "Just to pay my respects, just to touch your feet, just to be grateful. It has happened, and you have taught me that which cannot be taught."

This is what a master is to do: create a situation in which the thing happens. So only indirect effort can be made, indirect help, indirect guidance. And wherever direct guidance is given, wherever your mind is taught, it is not religion. It may be theology but not religion; it may be philosophy but not religion

(http://www.energyenhancement.org/vedanta/Osho-Vedanta-Seven-steps-to-Samadhi-Chapter-4-The-Supreme-Knowl edge.html)

It runs like this: The supreme knowledge cannot be taught. The disciple cannot know that there is something which cannot be taught. It happened in Upanishadic days that one young boy, Svetaketu, was sent by his father to a gurukul, to a family of an enlightened master, to learn. He learned everything that could be learned, he memorized all the Vedas and all the science available in those days. He became proficient in them, he became a great scholar; his fame started spreading all over the country. Then there was nothing else to be taught, so the master said, "You have known all that can be taught. Now you can go back."

Thinking that everything had happened and there was nothing else -- because whatsoever the master knew, he also knew, and the master had taught him everything -- Svetaketu went back. Of course with great pride and ego, he came back to his father.

When he was entering the village his father, Uddalak, looked out of the window at his son coming back from the university. He saw the way he was walking -- very proudly, the way he was holding his head -- in a very egoistic way, the way he was looking all around -- very self-conscious that he knew. The father became sad and depressed, because this is not the way of one who really knows, this is not the way of one who has come to know the supreme knowledge.

The son entered the house. He was thinking that his father would be very happy -- he had become one of the supreme most scholars of the country; he was known everywhere, respected everywhere -- but he saw that the father was sad, so he asked, "Why are you sad?"

The father said, "Only one question I have to ask you. Have you learned that by learning which there is no need to learn anything any more? Have you known that by knowing which all suffering ceases? Have you been taught that which cannot be taught?"

The boy also became sad. He said, "No. Whatsoever I know has been taught to me, and I can teach it to anybody who is ready to learn."

The father said, "Then you go back and ask your master that you be taught that which cannot be taught."

The boy said, "But that is absurd. If it cannot be taught, how can the master teach me?"

The father said, "That is the art of the master: he can teach you that which cannot be taught. You go back."

He went back. Bowing down to his master's feet, he said, "My father has sent me for an absolutely absurd thing. Now I don't know where I am and what I am asking you. My father has told me to come back and return only when I have learned that which cannot be learned, when I have been taught that which cannot be taught. What is it? What is this? You never told me about it."

The master said, "Unless one inquires, it cannot be told; you never inquired about it. But now you are starting a totally different journey. And remember, it cannot be taught, so it is very delicate; only indirectly will I help you. Do one thing: take all the animals of my gurukul -- there were at least four hundred cows, bulls and other animals -- and go to the deepest forest possible where nobody ever comes and moves. Live with these animals in silence. Don't talk, because these animals cannot understand any language. So remain silent, and when just by reproduction these four hundred animals have become one thousand, then come back."

It was going to be a long time -- until four hundred animals had become one thousand. And he was to go without saying anything, without arguing, without asking, "What are you telling me to do? Where will it lead?" He was to just live with animals and trees and rocks; not talking, and forgetting the human world completely. Because your mind is a human creation, if you live with human beings the mind is continuously fed. They say something, you say something -- the mind goes on learning, it goes on revolving.

"So go," the master said, "to the hills, to the forest. Live alone. Don't talk. And there is no use in thinking, because these animals won't understand even your thinking. Drop all your scholarship here."

Svetaketu followed. He went to the forest and lived with the animals for many years. For a few days thoughts remained there in the mind -- the same thoughts repeating themselves again and again. Then it became boring. If new thoughts are not felt, then you will become aware that the mind is just repetitive, just a mechanical repetition; it goes on in a rut. And there was no way to get new knowledge. With new knowledge the mind is always happy, because there is something again to grind, something again to work out; the mechanism goes on moving.

Svetaketu became aware. There were four hundred animals, birds, other wild animals, trees, rocks, rivers and streams, but no man and no possibility of any human communication. There was no use in being very egoistic, because these animals didn't know what type of great scholar this Svetaketu was. They didn't consider him at all; they didn't look at him with respect, so by and by the pride disappeared, because it was futile and it even looked foolish to walk in a prideful way with the animals. Even Svetaketu started feeling, "If I remain egoistic these animals will laugh at me -- so what am I doing?" Sitting under the trees, sleeping near the streams, by and by his mind became silent.

The story is beautiful. The years passed and his mind became so silent that Svetaketu completely forgot when he had to return. He became so silent that even this idea was not there. The past dropped completely, and with the dropping of the past the future drops, because the future is nothing but a projection of the past -- just the past reaching into the future. So he forgot what the master had said, he forgot when he had to return. There was no when and where, he was just here and now. He lived in the moment just like the animals, he became a cow.

The story says that when the animals became one thousand, they started feeling uncomfortable. They were waiting for Svetaketu to take them back to the ashram and he had forgotten, so one day the cows decided to speak to Svetaketu and they said, "Now it is time enough, and we remember that the master had said that you must come back when the animals became one thousand, and you have completely forgotten. Now is the time and we must go back. We have become one thousand."

So Svetaketu went back with the animals. The master looked from the door of his hut at Svetaketu coming with one thousand animals, and he said to his other disciples, "Look, one thousand and one animals are coming." Svetaketu had become such a silent being -- no ego, no self-consciousness, just moving with the animals as one of them.

The master came to receive him; the master was dancing, ecstatic. He embraced Svetaketu and he said, "Now there is nothing to say to you -- you have already known. Why have you come? There is no need to come now, there is nothing to be taught. You have already known."

Svetaketu said, "Just to pay my respects, just to touch your feet, just to be grateful. It has happened, and you have taught me that which cannot be taught."

This is what a master is to do: create a situation in which the thing happens. So only indirect effort can be made, indirect help, indirect guidance. And wherever direct guidance is given, wherever your mind is taught, it is not religion. It may be theology but not religion; it may be philosophy but not religion

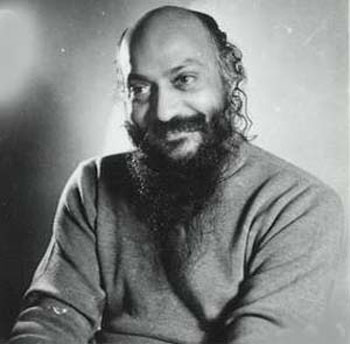

Acknowledgement: Some interesting pictures of Osho in his younger days !

It sets your mind in the thinking mode ...silent!

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete